Transnational Politics

Populism: The Paradox Between Increasing Localism/Nationalism and Transnationalism

I. Introduction

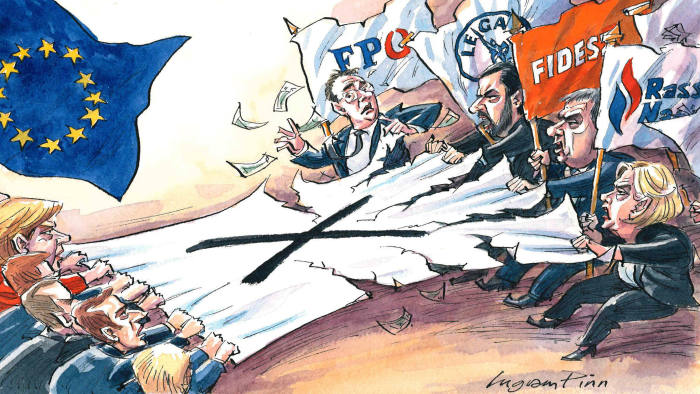

This essay will critically assess what appears to be a paradox between the increasing nationalism and transnationalism of populist parties. There is an increasing discussion on this in the light of the recent increase of nationalist/localist politics in the US, France, Hungary and Poland (Hartevald, 2020). It can be argued because these states were promoting transnationalism not long ago. They were joining the European Union (EU) around the millennium, and they were supporting open borders, migration and free trade. Yet, today when we look at them we see the reintroduction of border control and building walls. Most importantly, we see a powerful nationalist discourse focusing on the self-other distinction (Brubaker 2017: 1192; Hall, 2018).

In this study, to unpack this nationalist-transnationalist paradox in populist discourse, we will analyse this paradox through the case-study of France’s Front National Party, as Marine LePen’s discourse on liberal values (Human Rights, gender-norms) will help us best to uncover the contradiction of populist far-right’s approach on transnationalism.

II. Localism/Nationalism, Transnationalism and Populism

First, it is important to briefly look at the two sides argued to be contradictors. On the one hand, transnationalism is the process, goal and effects of globalisation, which are welcomed (Nye and Keohane in Hartevald, 2020). On the other, localism (or nationalism) aims to protect state-sovereignty, the domestic economy and cultural values (Hartevald, 2020).

In addition, populism is argued to be a group of ideas that builds on the division among ‘the good people’ and ‘the corrupt, evil elite’ in society (Mudde and Kaltwasser, 2018). It focuses on Christianism and secularisation (whereby Christianity is not about religious belief but is an indicator of identity, the belonging to a specific group of nation) (Brubaker, 2017).

We have seen an increase in these populist parties and in their support, particularly on the far-right (McDonnell and Werner, 2018; Muis and Immerzeel, 2017). Some regard this trend as a natural reaction to the effects that came with globalisation (Mudde in Hartevald, 2020). It is also important that radical-right voters are argued to be the ‘losers of globalisation’ who have an economically left- but culturally right-wing identity – and in populist argument, they are the majority, ‘the people’ (Kriesi et al. in Hartevald, 2020; Muis and Immerzeel,2017; Mudde and Kaltwasser,2018).

Regardless the cause behind, these populist parties need to be critically analysed in order to understand their behaviour and consequently, prospective consequences. Therefore, we must look at their paradoxical discourse on conservative and liberal values, what they prefer to follow in parallel with one another.

III. Populist Paradox: The Case of France

States, including France, promoted transnationalism since the formation of the United Nations and the EU. Yet, an increasing number of states have changed their discourse on regionalism and transnationalism. They argue against further shift in governance from the national- to the inter-national level, based on the sovereign power of the nation-state and the negative impact of globalisation on ‘the many’ (Muis and Immerzeel,2017; Mudde and Kaltwasser, 2018).

Yet, Marine LePen’s discourse contradicts with her right-wing populism: she has been campaigning to ‘protect the nation from the foreign threat’ but at the same time, she argues for the protection of the non-national values of Human Rights and gender-equality (Brubaker 2017). In addition, LePen does not intend to leave the EU, nor to offend its values that she protects, as we have discussed before (euronews.,2020). LePen is also against globalisation, – the one common ground among all populists, arguing how it subordinates nation-state sovereignty and creates many ‘losers’, – she wants to ‘re-nationalise’ politics. Yet, at the same time, she still cooperates with other-far-right populist parties beyond the national borders (LePen in Jan, 2018; Muis and Immerzeel, 2017; Mudde and Kaltwasser, 2018; Hartevald, 2020). Therefore, the paradox between nationalism and transnationalism finds confirmation.

IV. Conclusion

This essay has critically analysed the paradox of nationalism and transnationalism in populist far-right discourse. After briefly introducing the core concepts, our case study, LePen (the leader of the Front National Party) in France has highlighted the contradictory nature of populist discourse. First, EU member-states – like France – have joined the EU that is beyond the nation-state, and LePen declares no intention to change its membership (euronews., 2020). Second, we have uncovered how her discourse creates a paradox by arguing for the protection of national values and economy, alongside discussing the importance of the non-national values of Human Rights and gender-equality (Hartevald,2020). Last but not least, LePen’s actions of foreign-cooperation contradict with her localist arguments. Therefore, this study has confirmed and unpacked the paradox between the increasing localism/nationalism and transnationalism through populist far-right politics. Although, transnationalism has been popular after the end of the World Wars, it has come to an end and research must start to focus on the future of nation-states in the light of this development.

Bibliography

Brubaker, R. (2017) ‘Between nationalism and civilizationism: the European populist moment in comparative perspective’ Ethnic and Racial Studies 40(8) Taylor & Francis [online] pp. 1191-1226 Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2017.1294700 (accessed on 18/09/2020)

Euronews. (2020) Marine Le Pen: EU has more to lose on Brexit, but I don't want Frexit euronews [online] Available at: https://www.euronews.com/2020/02/06/marine-le-pen-eu-has-more-to-lose-on-brexit-but-i-don-t-want-frexit(accessed on 20/10/2020)

Hall, A. (2018) Critical Global Security Studies lecture University of York 15/11/2018

Harteveld,E. (2020) Transnational Politics lecture University of Amsterdam 21/09/2020

Jan, A. N. (2018) Globalisation and Its Impact on IPR Regime Student Paper Maharashtra National Law University Mumbai SSRN [online] Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3303841 (accessed on 20/10/2020)

McDonnell, D. and Werner, A. (2018) ‘Respectable radicals: why some radical right parties in the European Parliament forsake policy congruence’ Journal of European Public Policy 25(5) Taylor & Francis [online] pp. 747-763 Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1298659 (accessed on 18/09/2020)

Mudde, C. and Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2018) ‘Studying Populism in Comparative Perspective: Reflections on the Contemporary and Future Research Agenda’ Comparative Political Studies 51(13) JSTOR [online] pp. 1667–1693 Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414018789490 (accessed on 18/09/2020)

Muis, J. and Immerzeel, T. (2017) ‘Causes and consequences of the rise of populist radical right parties and movements in Europe’ Current Sociology 65(6) SAGE journals pp. 909–930 Available at: (accessed on 18/09/2020)

Comments

Post a Comment